| The

Parish Churches and Chapels in the Glasbury Area

This article was prepared by M. A. V. Gill in 2005 for the "Glasbury Book" (unpublished), It was first published with annotations in Brycheiniog Vol XVIII 2012 . The excellent artwork is also by the same local author |

| From "CHURCHES AND CHAPELS" by M.A.V.Gill This chapter will be dealing with local churches and chapels principally as buildings; but a church or chapel is more than an empty shell – it is a congregation of people who gather together in common worship, whether in prayer, praise and thanksgiving or in listening to the Word of God preached from the pulpit. At the beginning of the twenty-first century throughout the country many are in decline with waning numbers and ageing congregations. A hundred years ago the situation was very different: churches and chapels were all well attended, and each played an important role in the life of its community. J.W. Hobbs, reminiscing of his years as station booking clerk at Three Cocks (1902-1905), wrote that there were good congregations at St. Peter’s church, “chiefly the gentry, retired people, visitors at the Hotel, and some of the large farmers. Most of the working classes were chapel, except those employed at Gwernyfed or Tregoed. The strongest chapel was the Baptist at Glasbury, which was always full on Sunday nights, and often packed. Baptisms used to take place about once a year in the River Wye, which runs alongside the chapel. The chapel was the chief source of social entertainment. During the winter months was held what was called a Christian Union. The two Glasbury chapels and Felindre combined and held two entertainments in each chapel every winter. These always had to be arranged for the week of the full moon, so as to have moonlight on the way home. Our Three Cocks choir and band used to attend frequently. The chapel anniversaries were great events, both children and adults would take part and there were recitations and dialogues, solos, duets and quartettes. There were also frequent tea parties, lectures, Christian Endeavour and Prayer meetings, and concerts, but only on rare occasions were outside artistes engaged; we made our own amusements. Sometimes we would go farther afield, to Penrhoel or Maesyronen chapels or All Saints church, always on foot. We were not afraid of walking in those days;” GLASBURY CHURCH: SS.CYNIDR & PETER (A) THE MEDIEVAL CHURCH On 2nd January 1540, the monastery of St. Peter’s at Gloucester was suppressed and its privileges transferred to the King, who conferred the living of Glasbury upon the Bishop of Gloucester (patronage passing to the Bishop of St. David’s in the nineteenth century). Then, in 1545 Henry VIII sought new sources of revenue to finance his wars against France and Scotland; he determined upon the dissolution of chantries and similar institutions, but died before the act could be implemented. In 1547 under Edward VI a more comprehensive act was passed, the dissolution being justified on the grounds that “a great part of the Superstition and Errors in Christian Religion hath been brought into the minds of men by reason of the ignorance of their very true and perfect salvation, through the death of Jesus Christ, and by devising and phantasying vain opinions of Purgatory and Masses satisfactory, to be done for them which be departed”. The chantry at Glasbury was reported as being called “The Stoke”; it was “Founded to Fynde a Prest & he to have for his Salary by yere lvs to be taken out of the Stoke of mony which amontith to the summa of xiijli xvs”, and “Ys a service to be done within the said parish church”. During the Commonwealth period many clergy were ejected from their livings, among them Alexander Griffith of Glasbury. However, with the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 the Puritan nominee was in turn ejected and the legal incumbent returned to his parish. Around this time, the church was severely damaged by unusually high and violent floods, and was “in a most im’inent & inevitable danger to be utterlie demolished & destroyed (the one halfe of the steeple being alreadie undermined & fallen into the river, the churchyard (well nigh) to the very Church door, consumed & washed away, the graves opened, & the bones carryed away)”. Griffith wrote a petition signed by all the principal parishioners, requesting the Bishop “in this suddayne & unexpected exigency to impower & co’mand the Church Wardens of s’d parish to take some speedie & im’ediate course to draw down the rest of the s’d Church (itt being impossible to be theare p’served). That the materials may be secured & kept safe towards the building of another”. Unless speedy action were taken, “all the materialls of the s’d Church, as timber, iron barrs, windowes, freestones, lofts, seates & doores, w’ch amounteth to a great sum of money” would be “utterlie lost & taken away, the next or second flood, by the violence of the s’d river”. Permission was granted and the materials were salvaged, leaving only a depression in the ground to mark the original line of the walls. On the spur of land at the present confluence of the rivers Wye and Llynfi, the outline of the medieval church (slightly smaller than neighbouring churches at Llowes and Clyro) is clearly visible at the northwest corner of the large triangular mound. The Wye has changed its winding course many times over the centuries. Tradition has it that only a shallow rill passable on stepping-stones formerly separated the church from the village. A sworn presentment made at the New Radnor quarter sessions on 14th November 1561, refers to “the Castle and Castle Green from the west style of the churchyard to the bridge end”, and further notes that the bailiff is charged to enclose the land “from the west style of the churchyard of Glasbury to the corner of the great broad field and to keep all the scite of the lord’s mansion with the ground on the back side of the church between the church and the river to the west end of the bridge several to the lord’s use, and to set a gate for passage in the highway near to the said church style”. Clearly, at that date the river ran to the south of the church. In 1665 representatives of the parish explained to the Bishop at the consecration of the new churchyard that: ‘Heretofore wee had a Church uppon the other side of the water’. The statement is ambiguous; it suggests that although the great flood probably did result in certain changes to the course of the river, the violent shift of the Wye to the north that divided the site of the old church from the village may have happened somewhat later. (B) THE RESTORATION CHURCH The

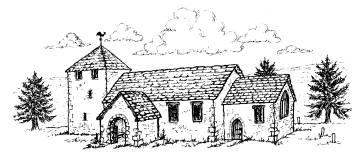

picture below is a Reconstruction of the Restoration church based

on descriptions Almost nothing remains of the 1665 church, apart from the lower courses of the chancel walls, some of the memorials and the altar rails. The latter were probably salvaged together with a cupboard-like communion table (replaced in 1881) from the medieval church, having been installed in the 1630s in accordance with an order from Archbishop Laud. Originally they bounded the table on three sides, their balusters set close together to prevent dogs that accompanied their masters into church from befouling the sanctuary. By the 1820s, the church was in a dilapidated state, and its seating capacity of 320 persons was considered too small for the increased population. Visitation returns in 1828 reported an average number in the congregation of about 500, the church being arranged “to contain not more than four hundred. Those over & above are uncomfortably situated”. It was therefore decided in 1836 to pull down the old church and erect a larger one on the same site, taking in part of the churchyard in addition. Legend (and it is no more than a legend!) says that worship continued in the old church while the new was built around it. (C) THE PRESENT CHURCH On Sunday 16th January 1887 fire broke out, the new stoves having become choked with soot. At the morning service the church “had seemed so cold that larger fires were suggested, and the Clerk being unwell, his wife replenished the same. On returning to the church to prepare for the evening service she discovered that the southern end of the building was on fire. She quickly summoned assistance, and after a short time the fire was got under, but not until considerable damage had been done. Some of the seats were totally destroyed, and a portion of the wall had to be knocked down to reach the flue”. Only a short service was held in the evening, “the smoke being so dense”! Another service conducted under trying circumstances was Harvest Evensong on Friday 26th September 1913. As the psalms were being sung “the water gave out at the organ, and the anthem had to be abandoned. The electric light under repair at the time also gave out so that the service lacked much of its usual brightness”! Source : -- "A Chapter on the Churches and Chapels in the Parish of Glasbury " by M.A.V. Gill |

The

earliest church in the parish of Glasbury was that of St. Cynidr,

probably founded by the early sixth century saint, whom tradition

says was buried here. Its precise site is uncertain; in all likelihood

it lay in the valley, near or beneath the remains of the Norman

church that replaced it. With the Norman Conquest, the manor of

Glasbury came into the hands of Bernard de Newmarch, who (with

thought for his soul’s salvation) in 1088 presented it to

God, to St. Peter and to the abbot and monks of Gloucester. His

heirs confirmed the grant of the manor, which included the church

of St. Cynidr with all its appurtenances. In 1144 the monks disposed

of the manor to Walter de Clifford in exchange for a manor in

Gloucestershire; however, they retained Glasbury church together

with its chapels, land and appurtenances. At some date the church

was rebuilt in stone, perhaps during the massive programme of

church building that occurred in the twelfth century, or following

the ravages of Llywellyn ap Iowerth in 1231; it may then have

been rededicated to St. Peter. The revolt of Owain Glyndwr at

the beginning of the fifteenth century necessitated substantial

repairs or a further rebuilding.

The

earliest church in the parish of Glasbury was that of St. Cynidr,

probably founded by the early sixth century saint, whom tradition

says was buried here. Its precise site is uncertain; in all likelihood

it lay in the valley, near or beneath the remains of the Norman

church that replaced it. With the Norman Conquest, the manor of

Glasbury came into the hands of Bernard de Newmarch, who (with

thought for his soul’s salvation) in 1088 presented it to

God, to St. Peter and to the abbot and monks of Gloucester. His

heirs confirmed the grant of the manor, which included the church

of St. Cynidr with all its appurtenances. In 1144 the monks disposed

of the manor to Walter de Clifford in exchange for a manor in

Gloucestershire; however, they retained Glasbury church together

with its chapels, land and appurtenances. At some date the church

was rebuilt in stone, perhaps during the massive programme of

church building that occurred in the twelfth century, or following

the ravages of Llywellyn ap Iowerth in 1231; it may then have

been rededicated to St. Peter. The revolt of Owain Glyndwr at

the beginning of the fifteenth century necessitated substantial

repairs or a further rebuilding. To secure the new church from the danger of future inundations,

a new site was sought. Land was given by Sir Henry Williams of

Gwernyfed, material salvaged from the old edifice, and in 1663

work began. Legend recounts that one day during Reconstruction

of Restoration church based on descriptions the building, the

farmers being busy with the harvest were unable to haul stone

for the church and left the carts full of stone. At dusk an enormous

white horse appeared, hauled the carts one by one to the church,

and disappeared with the dawn. By January 1665 the church was

finished (the first marriage and baptism being performed in the

middle of that month), although the church was not consecrated

until June 29th “being Sct Peters Day, & was soe called

St Peters Church”.

To secure the new church from the danger of future inundations,

a new site was sought. Land was given by Sir Henry Williams of

Gwernyfed, material salvaged from the old edifice, and in 1663

work began. Legend recounts that one day during Reconstruction

of Restoration church based on descriptions the building, the

farmers being busy with the harvest were unable to haul stone

for the church and left the carts full of stone. At dusk an enormous

white horse appeared, hauled the carts one by one to the church,

and disappeared with the dawn. By January 1665 the church was

finished (the first marriage and baptism being performed in the

middle of that month), although the church was not consecrated

until June 29th “being Sct Peters Day, & was soe called

St Peters Church”.

Lewis

Vulliamy, a London architect with local connections, designed

the new church on a larger scale. To those tendering for the work,

it was emphasised that the greatest economy needed to be observed

in the execution of every part of the new building, and no unnecessary

labour or materials were to be employed; old material was to be

re-used if sound, but in such parts of the church as would be

most out of sight and the cost of the three porches was to be

estimated separately. In the event, these were never built. Work

began in 1836 with stone coming from the adjoining quarry, and

the new church was opened for divine service on 23rd May 1838,

although it was not consecrated until 13th November. Further alterations

were carried out in 1881, when the west gallery was removed, the

chancel raised by one foot, the floors throughout the building

laid with encaustic tiles replacing the old flagstones, new seating

installed, and the windows re-glazed with “Cathedral glass

of a natural tint” (all but those above the north door since

replaced with stained glass). A space was left “for a new

organ which it is hoped will soon be forthcoming”; and a

new heating system was provided.

Lewis

Vulliamy, a London architect with local connections, designed

the new church on a larger scale. To those tendering for the work,

it was emphasised that the greatest economy needed to be observed

in the execution of every part of the new building, and no unnecessary

labour or materials were to be employed; old material was to be

re-used if sound, but in such parts of the church as would be

most out of sight and the cost of the three porches was to be

estimated separately. In the event, these were never built. Work

began in 1836 with stone coming from the adjoining quarry, and

the new church was opened for divine service on 23rd May 1838,

although it was not consecrated until 13th November. Further alterations

were carried out in 1881, when the west gallery was removed, the

chancel raised by one foot, the floors throughout the building

laid with encaustic tiles replacing the old flagstones, new seating

installed, and the windows re-glazed with “Cathedral glass

of a natural tint” (all but those above the north door since

replaced with stained glass). A space was left “for a new

organ which it is hoped will soon be forthcoming”; and a

new heating system was provided.