|

|

The Larger Gentlemen's Houses in the Glasbury Area |

Broomfield |

|

Gwernyfed |

|

Park Gwynne l |

Treble Hill |

Woodlands |

Introduction

The Big Houses project had been

on the History Groups mind for some time and was eventually kick-started

in late 2021; by an email from Mrs Ella Young which stated "My

mother’s side of the family owned Glasbury House and The Old

Vicarage for some decades".Her mother was Patricia Vulliamy

and Ella explained that she had lived in the old Vicarage in Glasbury

and had spent a lot of her childhood frequenting Glasbury House

and its grounds; and would we like to share her tales and photographs

for use on the web-site. This was the catalyst we needed and Chris

Forbes agreed to pursue the project with her usual vigor and exactitude

|

Glasbury

House - An

article by Chris Forbes (nee Lloyd)

For a village of its size, Glasbury has an unusually

large number of “substantial gentleman’s dwellings”,

one of which is Glasbury House in the centre of the village.

Glasbury House is a Grade II listed building which, between 1963

and 2019, was owned by Ilford Borough Council and the London Borough

of Redbridge who turned it into an outdoor activity centre. Since

2019 it has been the River Wye Activity Centre owned and run by

Rob and Claire Finley. However, prior to its sale in 1963 the

house was home to a number of families, some with very interesting

histories and connections – but more of that later.

The house was probably built in the early 1700s. According to

a family letter, written in 1843, the property was “mapped

and measured in 1734/5 as the property of Mr Howell Wynne”,

although it is certainly possible he was planning to remodel or

replace an older building already existing on the site.

The entrance drive from the main road bears round to the left,

to bring you to the oldest part of the house, a rendered elevation

of 2 stories. This (west) elevation has a plat band above the

doorway and 3 ground floor windows, indicating a mid-eighteenth

century construction. The upper floor has five 12-paned sash windows;

the lower floor has four 12-paned sash windows and the main doorway.

This central doorway has a Doric portico, now glazed in, and provided

with double part-glazed doors.

When the house was originally built there were 4 bays; the extension

at the southern end, comprising 1 window and a doorway, was added

by Redbridge in the 1960s to house a boiler room. This extension

is half as deep as the house.

The east elevation has 2 flat-roofed square bay windows to the

ground floor; there is also a door, over 2 steps, with a 20th

century pilastered and pedimented doorcase. Above, on the first

floor, are two 12-paned sash windows, one on either side of a

central Venetian window with intersecting glazing bars and crown

glass. Above this in the attic space are three segmental headed,

6-paned sash dormers with lead rooves.

The roof is of slate with chimney stacks of stone; dentilled cornice

eaves to the west elevation and modillion cornice eaves to the

east elevation.

The North cross wing is an addition of around 1840 – this

housed the kitchen and the nursery wing. Again it is of 2 stories

with two 12-paned sash windows and a six-panelled door within

a round-headed opening. An extension to the North cross wing was

built around 1975, with another flat roofed extension in 1993.

Much has changed inside the house, especially on the first floor

and in the attic space. However, on the ground floor the hall

retains decorative arches and there is an enriched cornice to

what was the drawing room. There is a well stair with a pilastered

dado. Visible in the cellar are ogee-moulded cross beams, perhaps

mid -18th century or reused from elsewhere.

A stable block to the south of the property was converted into

additional sleeping accommodation by Redbridge; the new owners

have also put in a café which is open to the public, and

offers breakfast for the campers using the grounds.

The house sits in grounds of just over 7 acres and is separated

from Glas-y-Bont by a stone wall which was built in the 1970s

as a flood wall. However, according to the letter written in 1843

(referred to above), Glas-y-Bont was originally part of the estate.

It had “from time immemorial belonged to the proprietor”

of Glasbury House and was, amongst other things, “a convenience,

an ornament and a protection against the river…”.

Thomas Hughes (see below) planted trees on Glas-y-Bont and his

wife used part of it as a potato garden. It would seem that the

Hughes family fenced in part of Glas-y-bont although this fencing

was destroyed in the great flood of 1795 which also carried away

Glasbury bridge. Glas-y-Bont ceased to be a part of the estate,

possibly at the time of the sale in 1953, and is now owned and

administered by Powys County Council.

The Hughes Family

Of the occupants of the house, the first family that we can name

with any certainty is the Hughes family – “a family

from Denbigh of great respectability and considerable opulence”

according to Theophilus Jones in his history of Breconshire, published

in 1805. Their connection with Glasbury dates back to Henry Rogers

who was vicar of Glasbury between 1684 and 1709. Henry Rogers

willed his “dwelling, outhouses, orchard, gardens and appurtences”

to his nephew, Howell Wynne of Denbighshire who had followed him

to Glasbury.

The property then descended, after Howell’s death in 1738,

to his nephew, Thomas Hughes who had also come to Glasbury from

Denbighshire. Thomas married Joan Williams, daughter of a vicar

of Glasbury, and they went on to have 14 children, the eldest

of whom, John (1741-1809), inherited after his mother’s

death in 1787. Another of their children, Bridget (1745-1824)

was a wealthy and benevolent woman who was instrumental in the

establishment of Glasbury Parochial School in 1816. This generous

act cost her £211 – the equivalent of about £23,000

today (2022). The school, later called Coed-y-Bolen school, continued

to educate the children of the village and surrounding area until

2012.

Although John, as the eldest son, inherited Glasbury House it

would seem that he did not live there; however, his sister Bridget

did. John trained to become a clergyman and was given the curacy

of Glasbury and Boughrood. He was a great horticulturist and distributed

a number of apple stocks round the village. One of these stocks

was the Carnation apple, of which there were a number of trees

in the village orchards and 2 still remain in Treble Hill orchard.

John died in 1809, leaving 3 daughters, and his

sister, Bridget, seems to have inherited the house. She lived

there with her widowed sister, Elizabeth Williams, and left the

house to her niece, Isabella, John’s youngest daughter.

Isabella died in 1845, leaving the house to her aunt Elizabeth

Williams for life, and then to Elizabeth’s daughter (and

her cousin), Bridget Papendiek.

The Papendiek Family

Elizabeth Hughes, the youngest daughter of Thomas and Joan and

sister of John, married Thomas Williams of Felinnewydd, Llandefalle

in 1781. Their daughter, Bridget, born in 1787, married in Glasbury

in 1810 the Rev. Frederick Henry Papendiek, vicar of Morden in

surrey. Frederick was the son of Christopher Papendiek, a violinist,

flautist and court musician to George III, and Charlotte (nee

Albert) who became Assistant Keeper of Queen Charlotte’s

Wardrobe and later her reader. Charlotte Papendiek published her

Memoirs, a record of events at court between 1761 (when the future

Queen Charlotte came to England to marry King George) and 1792.

The Papendieks knew many musicians, including John Christian Bach

(son of Johann Sebastian), William Herschel (who became an astronomer)

and Haydn. Charlotte’s memoirs also record meetings with

artists of the day, such as Thomas Lawrence and Thomas Gainsborough.

Her memoirs are a unique resource, recording significant information

about life at court such as living conditions, dress, education

and Anglo-German relations.

Sadly, Frederick died in 1811, a year after his marriage to Bridget

and before the birth of their daughter, Elizabeth Ann. Following

his death, Bridget Papendiek returned with her baby daughter to

live with her mother, Elizabeth, at Glasbury House, which she

inherited in 1846, and where she remained until her death in 1864.

The Vulliamy Family

Elizabeth Ann Papendiek married Lewis Vulliamy in 1838. Lewis

was a London architect; he designed the rebuilding of St Peter’s

church, Glasbury (1836 – 1838) in the Norman Revival style

of architecture.

The Vulliamy family originated in Switzerland; they became notable

as clockmakers in 18th and 19th century Britain, and as architects

in the 19th and 20th century. A "Vulliamy clock" was

presented to the Chinese emperor by the diplomatic mission of

George Macartney to Beijing in 1793.

When Elizabeth Ann inherited the house from Bridget in 1864, she

and Lewis did not live in Glasbury House, but rented it out. They

had 3 sons and a daughter and for some reason Glasbury House was

left to their daughter, Edith, rather than a son. She also did

not live in the house and eventually sold it to her brother, Edwyn,

who had lived in the village, in Parc Gwynne, since 1870. Edwyn

died in 1914 but his wife, Edith, continued to live in the house

until her death in 1953. Their son, Colwyn, was an author and

biographer. “Calico Pie”, the first

volume of his 3 part autobiographical novel has a critical, thinly

disguised account of life in Glasbury. He did not live in

the house in adulthood and after the death of his mother the house

was passed on to his son, John Vulliamy, who sold it to the Summers

family.

See Appendix 1 for John’s reminiscences of time spent at

Glasbury House as a child and young man.

The Summers Family

David and Phyllis Summers, who bought the house from the Vulliamy

family, were primary school teachers, originally from Tredegar

in South Wales. David was the Headmaster of Boughrood School.

They moved in with 3 of their children in 1953.

During their tenure, the local Civil Defence group met at Glasbury

House and occasionally the village fete was held there. They also

had Glasbury House licensed as a Country Club, with a bar in the

top lounge. Since Wales was “dry” on Sundays at this

time, it was a very popular Sunday venue for local members.

The village had a thriving amateur dramatic group, called the

St. Cynidr Players. The Summers were a driving force in this group,

with rehearsals being held, and scenery made, in Glasbury House.

Their plays were written and produced by a local playwright, T.C.

Thomas. They took part, with some success, in various competitions

and represented Wales in the final of the British Drama League

Competition in Glasgow in 1959. They did not win but came a very

creditable third.

David Summers suffered from ill-health and the family decided

to emigrate to Australia where, it was hoped, the sunnier climes

would benefit his health. The house was sold in 1963 to Ilford

and Redbridge.

|

|

Glasbury House from Glas y Bont in 1827

A painting by Usula Cooper from an original engraving

Courtesy of Brigid Edlin

Glasbury House frontage in 1865

- A painting by Ursula Cooper from a

photograph belonging to Patricia Drift Vulliamy - (Ella Young's

mother)

Courtesy of Brigid Edlin

Ella Young, by the Begwyns Trig

Point on her visit to Glasbury

in 2022 with her great friend Juliet Gayton.

Ella Young is the grand-daughter of C.E.Vulliamy

Photo courtesy of Juliet Gayton

A drawing of Charlotte Papendiek and her eldest son Frederick

in 1789

by Thomas Lawrence

Thomas Lawrence, Public domain, via Wikipedia Commons

Lewis Vulliamy and Elizabeth Ann Papendiek in 1855

A portrait by Alfred Edward Chalon (1780 - 1860)

Courtesy of Chistopher Vulliamy

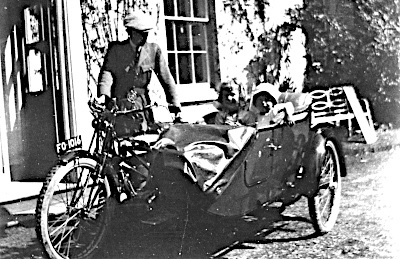

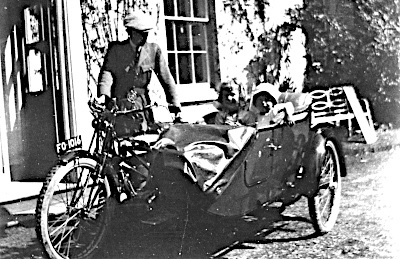

Colwyn E Vulliamy, author of Calico

Pie, with his daughter Patricia Drift

and son John Sebastion at Glasbury House in !922

Courtesy of Ella Young

David and Phyllis Summers in the 1960s

Courtesy of Cherill Theel (nee Summers)

|

Sources :

--

A great debt of gratitude is owed to Juliet Gayton for her work

on the histories of the families and house ownership mentioned

above, without which this piece could not have been written.

Ella Young

Census Returns

Cadw

Cherill Theel (nee Summers)

Wikipedia

Christine Forbes. August 2022

Appendix 1

A personal reminiscence, written by John Vulliamy

Glasbury House, or GHQ as it was known in the

family, was the paradise of my childhood and youth. Although spending

the first 5 years of my life, from 1919, at the Old Vicarage,

it was as a schoolboy that I really came to love the place. I

travelled “in charge of the guard” (he was tipped

half a crown!) from Paddington to Hereford: there I was met by

my favourite Glasbury friend, Percy Pugh the gardener. We boarded

the train to Glasbury station (that useful and beautiful line,

wrecked irrevocably by the wretched Dr. Beeching *) to be greeted

by Mr Miles, the smiling Station Master, surrounded by his bright

flower beds.

My grandmother, mostly bed-ridden for 65 years,

would be in her room (on the left at the top of the stairs). Although

she would on occasion get up in the afternoon her bedroom was

the hub of her life – and indeed of our family. She was

kind, shrewd and frugal, respected I think by the village (of

which she was “Lady of the Manor” – a title

she quietly enjoyed). She loved her telephone, which was her route

to the outside world. Dolly Morgan, the Post Mistress across the

river, managed the switchboard and was, of course, a great source

of all the local news and gossip which they avidly exchanged.

Most rooms in the house were linked by an internal

telephone system; anyone could be reached at any time, especially

those in the kitchen. Although by no means well-off (her deceased

husband had got through rather too much of the cash) she employed

a cook, parlour maid and the redoubtable gardener, Percy. I spent

a lot of my time in the kitchen and learnt much about life in

their company, especially from the talkative young women. The

room was dominated by a vast coal-burning range, a cosy sight

kept glistening with what I think was called black lead. My meals

were taken in solitary state in the dining room. It will seem

odd to the young people who currently come to Glasbury House to

think of this schoolboy ringing a bell to summon the parlour maid

who would serve his meals, wearing a white apron and cap! Would

there be fresh asparagus from the garden?

Candles were everywhere; I don’t know why

we didn’t have paraffin lamps; perhaps they were thought

dangerous. Lying awake in the nursery (the room over the kitchen)

I loved watching the movement of candlelight and shadows coming

through the open door as Percy and maids went off to bed; the

women had the room opposite my grandmother whilst Percy slept

in the attic.

The coming of electricity was a truly major event, around 1928

I think. It is hard to realise now what a huge impact this had

on the rural communities; to get light by touching a switch –

it seemed miraculous, comparable in its impact to the advent of

television several decades later.

I spent much of the day with Percy in the garden;

looking back he must have been very tolerant, putting up with

this boy’s chatter for hours on end. Within the house there

was so much to look at – the attics were my favourite place:

every wonder seemed to be there from guns, duelling pistols, swords,

spears and fishing rods to old newspapers, boxes of letters, ancient

cameras, photographic glass plates and carving tools: the residue

of generations. There were hundreds of books in the house, mostly

in the “smoking room” (men did not smoke in the presence

of ladies!) off the kitchen hall. They were mostly leather bound

and rather forbidding to my young eyes.

The place was handsomely furnished in good, solid,

comfortable early Victorian taste; some pieces contained carved

panels by my grandfather and on the walls were many paintings

by my father – his occupation before he became an author.

The bathroom was rather special because it contained a huge wood-lathe,

complete with wonderful sets of tools, work-benches and so on.

It was in this room that the dentist, with his foot-operated drill,

would make an occasional visit to minister to the household. It

was a painful activity in those days.

One less congenial thing I had to undertake was to visit a number

of old ladies who befriended my grandmother in the village. They

were dear old folk no doubt and most kind (and unduly respectful

to “Master John”- yes, really, that was how this little

boy was addressed!) but it was a bit of a strain. I felt, nevertheless,

it was a duty to try and be jolly and polite and to be enraptured

by all the local gossip in which I was not in the least interested.

Wandering about in the stables was a great pleasure.

There was a splendid carriage, still shiny and comfortable, complete

with ivory window fittings; once it was harnessed and driven out,

with my grandmother on board, into the village somewhat to my

embarrassment. There were 2 Bath chairs, one enclosed by mahogany

and glass and rather intimidating, the other open and very comfortable

in which I occasionally pulled my grandmother around the garden

at high speed – greatly to her alarm. The chickens gathered

round the stables to be fed; they were a fine lot and spent the

night roosting high up in the trees. I don’t think it worried

me that I might well be eating one of them the next day. There

were 2 canoes – one made by my grandfather – and paddling

about on the then deserted river for hours on end was without

question one of the great joys of Glasbury.

Percy and I would make occasional trips up the

Black Mountains, cycling to the foothills; my enduring love of

the countryside stems I suspect from these experiences. We did

not always behave too well; my favourite pastime was rolling flattish

stones down the hills, watching them leaping and bouncing at great

speed, scattering terrified sheep in the process! In less dramatic

vein was the daily visit to the shop across the road run by Jenkin

Morgan and, later, his sons Hector and Roche. It seemed to contain

all our needs and I remember well Hector wrapping a pound of sugar

from a huge bin so dextrously into a piece of dark blue paper,

never spilling a grain. Sometimes Percy and I would go by train

to Hay; quite an event; it was usually to visit Mr Nott the chemist.

It was then a sleepy little market town – no bookshops,

all that was to happen much later.

Yes, it was paradise indeed and I was always

sad to leave and return to our home in London. The moment of parting

was, however, always softened by my dear grandmother slipping

me a couple of pound notes – a fortune to a young boy in

those days.

In conclusion I must say how delighted I was

to hear not long ago that the Borough of Redbridge had subsequently

bought that much loved place. The use to which it is now put is

so splendid. The old house has surely never served a better purpose,

giving pleasure to so many young people.

September 1999

* Glasbury Station was sheduled to be closed

just before the Beeching period.

|

| |

|