| The

Glasbury Bridge Legal Dispute This Article was researched and written by David Edlin of Treble Hill Cottage Click on this line to see the law report of 1847 and extracts from the Parliamentary Boundaries Act |

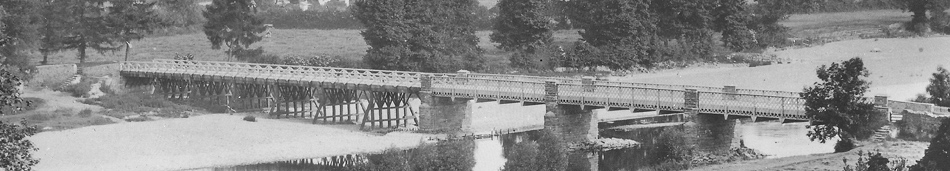

The Bridge in the late 1800s, after the settlement of the dispute - Courtesy of Frank and Geraldene Cleary |

THE COUNTY BOUNDARY AT GLASBURY: A CASE FOR THE

QUEEN’S BENCH The old parish of Glasbury straddled the counties

of Brecon and Radnor, but the local boundary between the counties

was not the River Wye. Part of the parish on the right bank of the

river – an area of 470 acres – was in Radnorshire. In

1844 that changed. The Counties (Detached Parts) Act of that year

transferred the 470 acres to Brecon. But because of the poor drafting

of the relevant legislation there was at the time doubt about whether

the transfer had been successfully effected. The uncertainty needed

an early resolution because the right bank half of Glasbury Bridge

was in disrepair. Who was responsible for repairing it? Brecon or

Radnor? The question had to be decided in court. At the top of the

page there is a link to the law report of the court case. Why the Glasbury entry in Schedule M was worded as it was must be a matter of speculation. The reference in the third column, which was meant to identify the county in which the “isolated” part was locally situated, to “Brecknockshire or Radnorshire” might possibly be a mistaken consequence of the fact that the right bank part of Glasbury Parish had been partly in Brecknockshire and partly in Radnorshire. The question, “what county is the right bank of Glasbury Parish in?” could have been answered, albeit unhelpfully, “Brecknockshire or Radnorshire”. If the draftsman, or someone briefing the draftsman, had proceeded in the mistaken belief that the “isolated” part was the entirety of the parish on the right bank, that could explain why the third column was completed as it was. An alternative explanation is that “Breconshire or Radnorshire” was meant to express the fact that the “isolated” part was situated between Brecon and (the rest of) Radnor. None of this speculation offers an explanation of why the first column of the schedule was wrong. Nonetheless, initially the efficacy of the Act

was not questioned: it appears from the findings of the court that

while before the 1832 Act voters in the 470 acres had voted for

a knight of the shire (country MP) for the county of Radnor, following

the Act they were registered and voted for a knight of the shire

for the county of Brecon. First there was an attempt to get the case dismissed for a procedural reason. It was argued that the right of a single magistrate to present a county bridge out of repair had been abolished by legislation, so the case had not been properly brought and should be quashed. This point was argued in London in 1849 before a court presided over by Chief Justice Denman. In short, he was unimpressed with this procedural objection and decided that the case should go to trial. Secondly there was a trial at Hereford Summer Assizes in summer 1849. This was a trial with a jury and was presided over by Baron Rolfe. Its purpose was to establish the facts of the matter, leaving the legal arguments for the third stage of the proceedings. (“Baron” was the judicial title of the judges of the Court of Exchequer – see Notes below.) The findings of fact are set out in the report from page 817. It was established that historically the county boundary above and below Glasbury was at the mid-point of the Wye, but at Glasbury it left the river to take into Radnor the 470 acres on the right bank. The boundary “proceeded from the mid-channel to the right bank… at The Staunces, and then, first in a south easterly direction for about a mile, and afterwards in a north easterly direction for about three quarters of a mile, through the portion of [the parish] which is situate on the right bank to a place called Healygare [Heol-y-Gaer], on the confines of the parish of Llanigon… and then returned along the boundary of the said parishes of Glasbury and Llanigon, to the mid-channel of the said river at a point where the said river Wye passes out of Glasbury parish.” At page 820 is set out what had happened as to the 470 acres since the 1844 Act. No part of the area had been assessed for the county rate for either Brecon or Radnor! But the poor and highway rates continued to be collected by Radnor and those qualified to serve on juries were on the Radnor list not the Brecon one. The third stage of the case was argued in London the following year. The essence of the argument for the Crown was that while the description in schedule M to the 1832 Act was inaccurate, the legislature clearly meant to annex some portion of Glasbury to Brecknockshire and that portion was either the 470 acres… or nothing. The intention of the legislature was sufficiently plain despite the inaccuracy of the schedule. The primary argument for Brecon was that, to paraphrase, the muddle was too great for the intention of parliament to be guessed at, the court should not proceed upon what would amount to a re-writing of the schedule and the failure of the Act in this particular should be accepted as such. There was a secondary argument: if the schedule could be construed as operating to transfer land to Brecon, it did not follow that the new boundary should be at the centre of the river. What had isolated the right bank land was the river, so the new boundary should be the right bank. If that was right, the whole width of the river would have remained in Radnor and so Radnor would have to repair the bridge. The court was unimpressed with Brecon’s argument.

The judges did not ask counsel for the Crown to reply to Brecon’s

arguments: they had already formed their view. You can see which

way the wind was blowing from Mr Justice Erle’s intervention

during Mr Phipson’s argument for Brecon (begins at the bottom

of page 823). The court was going to take a purposive approach to

the interpretation of the schedule. The repair of the bridge was

found to be Brecon’s responsibility. Mr Justice Coleridge

did however pay Mr Phipson the compliment of describing his secondary

argument as “ingenious”: he had done his best with a

losing case. 6. The titles of the Acts in the law report follow the then practice of identifying statutes by reference to the year of the monarch’s reign in which they were enacted. 1832 straddles the second and third years of the reign of William IV, hence “stat. 2 & 3 W .4. c. [chapter] 64.” It was only in the last decade of the nineteenth century that “short titles” to Acts, using the calendar year, were introduced. Existing statutes were given short titles retrospectively.

|